Many things can be attributed to Sally Ride. She was the first American woman in space. She was also the youngest at the time of her initial flight in 1983. Before that, she served as the ground-based CapCom for the second and third space shuttle flights, and helped develop the shuttle’s robotic arm; after that, she was the only person to serve on both panels investigating first the Challenger, then the Columbia, disasters, and co-founded Sally Ride Science, a company that developed educational programs for students, with an emphasis on girls. She posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013. She was a trailblazer, especially for women, who— at a time when women working in scientific field were an anomaly, and the only American astronauts for years were white men— saw in her that the seemingly impossible was achievable.

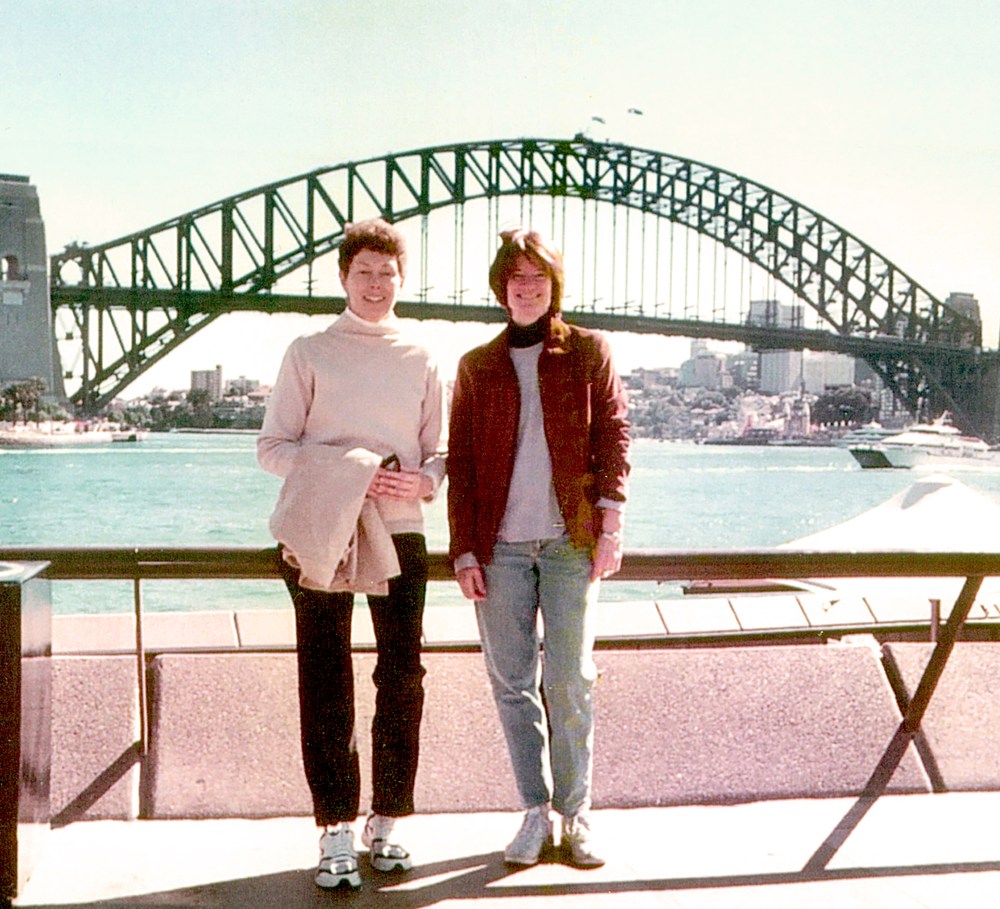

But despite being, for a time, one of the most famous people in the world, Sally maintained a secret that didn’t become public knowledge until after she passed away from pancreatic cancer in 2012: she was also the first astronaut known to be LGBTQ, and was in a relationship with educator and former pro tennis player Tam O’Shauhnessy for 27 years. Cristina Costantini’s simply titled documentary Sally attempts to marry these two narrative threads, centering her film around an intimate interview conducted with O’Shaughnessy, who became close friends with Sally when they met as preteens before reconnecting and falling in love later as adults.

Costantini’s approach to her subject— new interviews not only with O’Shaughnessy, but also Sally’s mom Joyce and sister Bear, ex-husband and fellow astronaut Steven Hawley, and some of her other surviving NASA colleagues, along with plenty of archival footage and interviews with Sally— is straightforward and consistently engaging. When Sally joined NASA in 1978, it was part of the first group of women and people of color to enter the space program. The sexism she constantly faced, particularly in interviews where the media’s primary focus was on the fact that she was a woman. You can almost see the weariness on her face as she declares that her gender shouldn’t be all everyone sees and talks about, that if all was right in the world, it wouldn’t be a point of discussion at all. It’s frustrating to watch conversations we’re still having today occurring nearly 50 years earlier, but the film has some fun with NASA’s cluelessness as well, accompanying the engineers’ query as to whether 100 tampons would be sufficient for one week in space with a cheeky kaleidoscopic montage of hundreds of the sanitary product dancing across the screen.

These interviews are pivotal in allowing Sally to still have a prominent voice in the film. But while O’Shaughnessy’s spunky personality and tender memories of Sally— the specificity of remembering that the very first time she ever saw her, it was at a tennis meet and she was walking on her tip-toes, for instance— lend the doc an essential personal angle, it’s in exploring the side of Sally that isn’t as well-documented that Sally commits a fatal non-fiction filmmaking misstep: making assumptions about its subject’s thoughts and feelings and decision-making in the absence of that subject being present and able to speak for herself. Too often, particularly in the back-half of the film when the narrative pivots largely to Sally’s life after NASA and her relationship with O’Shaughnessy, the interviewees speculate as to why she remained in the closet for so long (compared to O’Shaughnessy, who was out and proud before she got together with Sally, and whose partner’s secrecy about her sexuality she admits to finding oppressive). Sure, it would have been huge had a public figure as prominent as Sally been out at the time. It also isn’t fair to make so many leaps about her reasoning, especially when taking into account how dangerous the environment was for LGBTQ+ individuals through the 1980s and into the 90s. As thoroughly as Sally examines gender politics, it never pulls back enough to look at the landscape for queer people at that time in history as a whole to provide viewers with the necessary context. The film’s perspective is further manipulated by the inclusion of staged interludes in which actors are used to visually illustrate Sally and O’Shaughnessy’s relationship (sitting together on a bed the first time they shared a kiss, or dancing together to Neil Young’s “Harvest Moon” as their time together neared its end). These moments are brief and not overused, but they also contribute a cloying sentimentality to the film that it doesn’t need.

Sally Ride— and Tam O’Shaughnessy— deserve to be talked about and learned about. And Sally, as rote a bio-doc as it may be,gets halfway there toward giving her the tribute she deserves. But it’s unbalanced dissection of her sexuality leaves the film ending on a frustratingly skewed note.

Sally premieres on National Geographic on June 16, and will be available to stream on Disney Plus and Hulu beginning on June 17. Runtime: 103 minutes.

I really love the thoughtfulness, knowledge, and writing of your reviews. You back up your opinions with so much knowledge of the industry and appreciation of the craft.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike