A camera sweeps over the imposing Kazakhstan landscape, tracing the path of a lone figure walking amid the rock formations, a falcon flying overhead. The music swells as the camera pushes in close on this man, grandly philosophizing through his solemn voiceover narration. It’s an opening scene fit for an epic action movie, but Once Upon a Time in Uganda—the title recalling similarly-named classic action/adventure movies—isn’t exactly that. Rather, it’s a documentary about the epic making of epic action movies, specifically those created by filmmaker Isaac Nabwana and his Ramon Film Productions. Nabwana and his team may have next to no money at their disposal, but with a little ingenuity and a lot of love for their craft, they cobble together what they have on hand to create some of the most unique, gonzo action flicks around. Nabwana’s home of Wakaliga, Uganda was dubbed Wakaliwood as a result, his films becoming cult hits worldwide as their trailers picked up steam on YouTube.

That man in the opening scene isn’t Nabwana, however. That’s Alan Hofmanis, a white American film programmer and producer whose friendship and partnership with Nabwana is the linchpin of the narrative of director Cathyrne Czubek’s film. Nabwana may be the one making movies, but Hofmanis’ life sounds like one: he was in a long-term relationship with his girlfriend, but the day he purchased the wedding ring was the day she left him. When a friend showed Hofmanis the viral trailer for the Wakaliwood movie Who Killed Captain Alex?, he knew before the video was over that he needed to go to Uganda, needed to meet the man who created this crazy and fresh piece of action cinema. Feeling unfulfilled at his current job, Hofmanis sold all his belongings, dropped his cat off with his mom, and made the move from the Big Apple to the “Home of Da Best of Da Best Movies.”

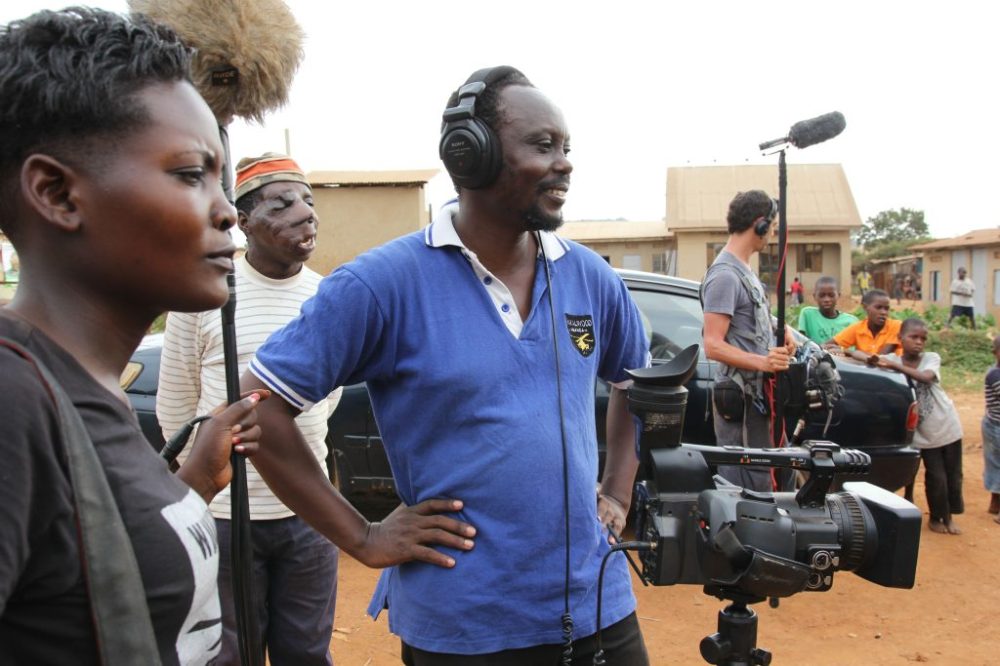

Once Upon a Time in Uganda relies heavily on reenactments of real events to portray how Hofmanis and Nabwana linked up, often with a playfulness akin to the films themselves; at one point, Czubek stages a grand chase through the market streets depicting Hofmanis spotting and chasing down a man wearing a Ramon Film Productions shirt and selling DVDs of their movies to passersby, finally convincing this man to take him to Nabwana. Hofmanis ends up befriending Nabwana and becoming a key member of his team, taking over some office duties to free up time for Nabwana to make movies and reaching out to programmers and potential investors around the world to get them to see what he saw about these movies that is so magical. Other moments later in the film—intimate conversations between Nabwana and Hofmanis about the diverging directions they want to take their work in, for instance—come off as too staged for the camera to be wholly effective. But the doc otherwise largely utilizes on-the-ground footage shot from around 2015 onward to provide a sense of the inner workings of a Wakaliwood production, and the quality of life there.

Once Upon a Time in Uganda sings the strongest when it focuses on the actual behind-the-scenes making of one of Wakaliwood’s movies. We get glimpses into their prop room—brimming with play guns and tricked-out vehicles donated to the crew and camera rigs welded together using whatever parts they had—and editing suite, where charmingly rudimentary effects are added to footage of volunteer actors shot against a green screen. We see light makeup being caked onto a Ugandan man so he can serve as Hofmanis’ stunt double. As the resident white man, Hofmanis—who the Ugandan residents soon nickname “Chuck Norris”—becomes a star of the movies in his own right, helping Nabwana kick-start a popular subgenre of his films that they straightforwardly dub “beating up the white person.”

However, Once Upon a Time in Uganda fails to get at precisely what makes Wakaliwood action movies such distinct and enjoyable entertainment, outside of some brief discussion of the video jokers, or VJs (these are narrators who lay tracks over the footage, humorously commenting on what is unfolding onscreen and adding layers of comedy to the action). The film is more concentrated on the finance and distribution side of production, which is often eye-opening in its own right, if less compelling. A common thread repeated throughout the documentary is the fact that Nabwana’s movies don’t turn a profit. A former bricklayer, he pays the bills by shooting commercials and weddings. Eventually, his wife Harriet—who he roped into becoming the head of the studio after marrying her, passing on to her his love of movies—starts a business making cakes. Wakaliga is in the slums (the lack of electricity is an issue), and Nabwana says early on that going to the movies is a rich people’s activity; as hard as it is to get the movies made, it’s just as hard to get people to pay to watch them. Even after Hofmanis’ outreach efforts bring Wakaliwood to the international stage, with coverage from major news outlets, they still don’t receive any offers from potential investors. It’s an endless, vicious cycle that any artist can relate to: the love of creating versus the struggle to make the time and money to be able to do so. And as much as people love to say that they champion independent film and minority voices, those with the money and power to elevate those voices frequently don’t.

Once Upon a Time in Uganda ends up following Hofmanis at least as equally as it tracks Nabwana, and that leads to the film feeling rather scattered in its second half. We’re told of the rift that forms between the two men before they are ultimately pulled back together, but we don’t really see or feel the build up to that. Viewers who have never seen a Wakaliwood movie before watching this documentary may leave still a tad confused as to just what their films are like, and yet, when Nabwana walks out to a full, 1,200-strong audience when his 2016 movie Bad Black screens as part of the Midnight Madness program at the Toronto International Film Festival, you’d be hard-pressed not to shed a tear at seeing this man whose passion we’ve borne witness to for the last 90 minutes receiving the love and attention he so richly deserves. There’s another scene earlier in the film that feels like it was lifted from one of those more serious “love letter to cinema” type movies, but just as equally conveys how much movie-making is a family affair for Nabwana: he hold up strips of film for his children, using a small light to project the images against the wall of their home as the kids pepper him with questions and observations. If Once Upon a Time in Uganda successfully coveys anything, it’s that art brings communities together, and that there’s nothing like the communal joy that stems from making and sharing movies with your loved ones.

Once Upon a Time in Uganda is playing in select theaters nationwide, and will screen locally at Arkadin Cinema & Bar on July 14 and 15. Runtime: 94 minutes.