The Berlinale‘s Panorama sidebar is typically home to the festival’s most daring works in contemporary international cinema, spotlighting both debut filmmakers and established directors. The following films making their world premieres in this year’s Panorama section run the gamut from lyrical character studies to historical dramas to documentaries about global conflicts in the news right now. Read my reviews of Paradise, Narciso, and A Russian Winter below.

Nothing and no one are as they seem as they reach for the elusive promise of Jérémy Comte’s feature film debut Paradise. Two teenagers, separated by an ocean but united in the absence of their fathers and their scraping to build a better future for themselves and their loved ones, are at the center of this mesmerizing and puzzling drama that reaches for a poeticism it never fully grasps.

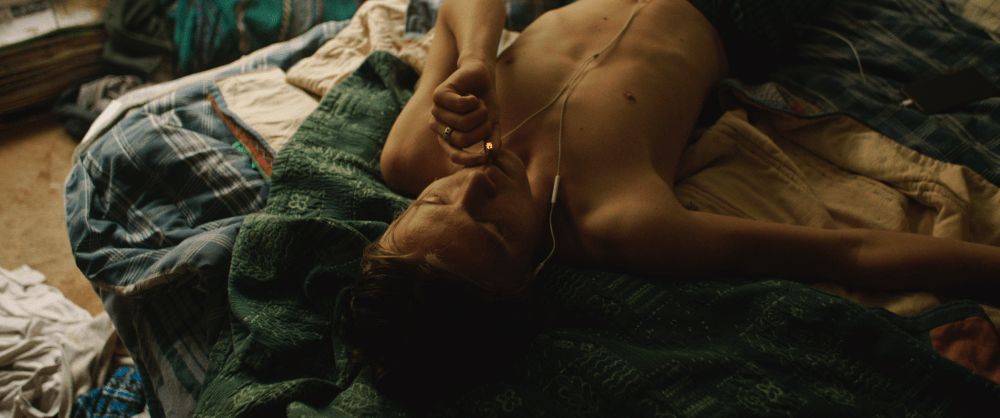

The film establishes its lyrical rhythms from its storybook-like division of the narrative into three distinct chapters, and its opening scene, in which images of a boat sinking, flames licking its frame as its inhabitants jump overboard, are viewed from the shore of a tranquil beach, accompanied by soft voiceover narration. We first meet Kojo (Daniel Atsu Hukporti Adjorble), a teenager who’s beguiled by the easy money to be earned from gangs and scam artists working the bustling streets of Accra— Ghana’s capital city— where he lives, driving a rift between he and his father, a fisherman who values tradition and taking pride in your craft. Meanwhile, in Quebec, Tony’s (Joey Boivin-Desmeules) rebellious streak is more typical of most teens; he spends much of his free time skateboarding and smoking weed with his friends, but he still enjoys an easygoing relationship with his single mom, Chantal (Evelyne de la Chenelière). Unbeknownst to Tony, Chantal’s giddiness (she implores Tony to take photos of her seemingly at random) is due to the fact she’s been seeing a boat captain she met online for several months. Tony and Kojo’s worlds collide when the captain’s boat supposedly sinks off the coast of Ghana, leaving him injured and plying Chantal for money to get him out.

Olivier Gossot’s cinematography effectively communicates the difference between Paradise’s two key locations: the chilly, muted tones of Canada stand in contrast to the warm, saturated environment of Africa. Even before they meet, the twists of Comte and co-writer Will Niava’s script subtly reveal how Kojo and Tony essentially mirror each other. They’re both looking for father figures, Tony suspecting his mom’s mysterious captain may be his real dad, Kojo grappling with his own father’s disappointment. They’re both trying to work their way toward a better future, and they’re both in over their heads, Kojo because he was too quick to show off the wealth he gained from running catfishing scams (a tangential scene in which in which some younger boys are shown how it’s done illustrates the ease with which technology can be employed for deception, especially when those being targeted are lonely and vulnerable), Tony because he decides to take action to right the wrong done by his mother. Recurring images of fire and water tie these seemingly disparate plot threads together, while foreshadowing the very real accident whose effects will further ripple across the globe. Paradise wraps up rather too quick and neat to truly hit the emotional heights the visuals and Valentin Hadjadj’s overwrought score are clearly straining to reach by its climax, where simple trust in the actors and a screenplay that fleshed out their dynamic further may have accomplished more. But it remains a hypnotic and dreamlike rumination on the impact of the illusions we craft to move forward with our lives— looking for parents or lovers or opportunities where there are none to be found— and the unexpected connections that ultimately transcend physical distance.

In 1959— five years into Alfredo Stroessner’s 35-year dictatorship— Narciso (Diro Romero) returns to his home in Paraguay after a trip to Buenos Aires exposed him to rock-and-roll, forever altering the course of his life. He convinces the owners of a radio station, Manuel (Manuel Bermúdez) and his wife Elvira (Mona Martínez) to shake up their usual program of folk music and radio dramas with a new show tailored to young people and drawing on the music that was making waves in America at the time: Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard. Narciso isn’t a musician, however. He’s just a very charismatic and enthusiastic guy who channels those traits into hosting a show where he pumps up the crowd by announcing the next track the DJ is about to play, swiveling his hips along to the songs to the exuberant shrieks of the teeny-boppers in the audience.

Despite this different twist on the typical music biopic, writer and director Marcelo Martinessi’s Narciso proves to be about as routine as they come. It’s a fictional narrative, but Narciso is based on Bernardo Aranda, a 27-year-old Paraguayan radio host who was found dead in an apartment fire. The case has never been solved. Was it an accident? Was it suicide? Or did the rumors that Aranda— a popular media figure— was gay trigger the oppressive regime to swiftly eliminate him?

Narciso attempts to flesh out the possible conflict while demurring from settling on any concrete resolutions, beginning with a death before flashing backward. It’s a film built on maybes, not only regarding Aranda, but also because so few visual records of 1950s Paraguay survive. The vintage production design is rather spare, with the bulk of the film unfolding in interiors, and cinematographer Luis Arteaga often turns the camera toward the shadowy corners of the frame— a fitting approach, as the country’s queer culture was forced to meet clandestinely to avoid persecution. Desire and intrigue simmer throughout the scenes following Narciso and Manuel through these underground spaces. They’re juxtaposed with a recurring segment in which the radio station mounts a production of Dracula, sitting in intriguing if perhaps overtly explicit conversation with the contemporary political regime’s meeting sexual transgressions with violent punishments, although the film neglects to detail the horrible real-life repercussions of Aranda’s death: the government and law enforcement weaponizing the murder investigation as an excuse to target the LGBTQ community, leading to the persecution and torture of over 100 gay men in what later became known as Case 108.

Ultimately, Narciso the film tackles too much (even American imperialism emerges as an undercurrent by the film’s final scene, in which running water comes to Paraguay for the first time courtesy of a project promoted by the U.S.) and emerges with too few conclusions, beyond the admirable perseverance of art and artists when confronted with censorship and authoritarianism. And Narciso the man, despite his apparently massive on-screen following, remains too enigmatic a figure for the audience to grab on to.

Patric Chiha’s loose and experimental documentary A Russian Winter turns its gaze to a lesser spoken of side effect of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine: the young Russian citizens whose refusal to comply with the regime’s human rights violations means they must face jail or exile from their home country. This largely conversational film is cycles through the stories and perspectives of a handful of individuals, but quickly finds its center in the friendship between Russian outcasts Yuri and Margarita, who initially aided Chiha in translations on his film before becoming a key subject in her own right. With no place to call home, they exist in a perpetual liminal space, drifting from country to country, living out of a handful of bags and belongings kept in storage units, the fear of being found out and arrested always sitting at their shoulder. The surreality of their lives is accentuated by the film’s experimental aesthetic; in the opening montage, for example, negative photography illustrates how everyday life in Moscow has been inverted.

A Russian Winter opens with Yuri, a musician in his mid-30s who never relinquished the rebellious streak of his younger days (Yuri’s involvement in the film extends to scoring its soundtrack, imbuing the documentary with a punk vibe that matches its subjects). Despite the film’s washed-out tones that frequently divorce what is seen on screen from reality, Chiha’s directorial approach is largely traditional, training his camera on his subjects for long stretches, allowing the power of their stories to speak for themselves. Early on, Yuri discusses how his father essentially disowned him for his political beliefs; he subsequently joined the Russian military and was killed in a conflict. It’s an effective demonstration of the lines the war drew between families, particularly those of different generations. Midway through the film, the focus shifts to Margarita, who is stuck in Istanbul waiting for her visa to be approved so she can join Yuri in Paris. As A Russian Winter rolls on, and the days for these characters stretch and blur together, the nature of these endless conversations swirling around the nature of displacement and estrangement become more repetitive and therefore less impactful. The challenge to this film is that there really isn’t an end to their story, at least not yet. But the aimlessness of the movie is also sort of a nice parallel to the aimlessness of its subjects, who— as uncertain as their existences have become— find at least a modicum of solace in the community of like-minded exiles they’ve cobbled together.