Stories of family, both of the blood and found variety, have populated many of the programmed features at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival. Below are three of them representing familial tales from different cultures and various parts of the world making their world premieres at the festival: Don’t You Let Me Go, Color Book, and Bitterroot.

DON’T YOU LET ME GO

At the start of Don’t You Let Me Go, a drama from the Uruguayan writing/directing team of Ana Guevara & Leticia Jorge, Elena is dead. Her friends and family have gathered for her funeral. That strange, liminal space the living are left to inhabit when a loved one passes away is effectively conveyed by Guevara and Jorge in the film’s opening shot: a pair of young children running and giggling across a building lobby toward the camera, collapsing in exhaustion on chairs in the foreground, while in the background, a group of people wheel a casket in and out of the frame. From there, the camera unobtrusively weaves in and out of pockets of conversations: sudden tears and laughter that burst seemingly out of nowhere, expressions of disbelief that she’s gone, gossip over the identity of other funeral attendees, and memories of times shared, both good and bad. It’s about as real a depiction of those various early waves of grief as it gets.

After the free-floating first 17 minutes or so of Don’t You Let Me Go (which is divided into chapters), the narrative shifts focus more exclusively to Adela (Chiara Hourcade), Elena’s best friend. When Adela gets in the car to leave, she’s confronted with a sign of Elena and a magical bus awaiting her, and the general disconnectedness toward her surroundings she exhibited at the funeral gives way to a journey into the past, to a summer years ago, when Elena (Victoria Jorge) is still alive, and the two companions are joined by their fellow friend Luci (Eva Dans) and her baby son Paco. Much like the funeral, summer vacation often indicates a liminal space in time, where hours and days spent in carefree indulgences easily slip away. For Adela and Elena, this means riding bikes by the ocean and lazying away reading mystery novels. They’re adult women here, but there’s something childlike in them that this nostalgic era awakens (their paranoia about an intruder likely brought about by reading all those detective novels, for example, or Luci’s sometimes almost flippant parenting). These scenes are light and hazy, especially compared to Don’t You Let Me Go’s first chapter; it’s evident here why Guevara and Jorge originally titled the film Three Women and a Baby, a phrase with associations to broad comedy, but ultimately, their movie isn’t that. There’s always a sense in the interactions between the three women that their time together is ticking down. This time-travel experience, which is so beautifully transitioned to between chapters one and two by a series of shots of the changing landscape zooming past the bus window (the filmmakers cite the Catbus from another film about grief, My Neighbor Totoro, as a primary inspiration), serves as a way for Adela to, perhaps not let go, but process Elena’s premature loss. Guevara and Jorge, who met at university and have collaborated ever since then, possess a clear vision, especially with framing, and the ability to write such a layered, personal story that can only come out of a close partnership. Brought to life by a lively cast whose ease with each other makes them completely believable as spiritual sisters, Don’t You Let Me Go is a slippery but no less moving excavation of friendship, sorrow, and life itself.

Don’t You Let Me Go had its world premiere at the 2024 Tribeca Film Festival on June 8. Runtime: 74 minutes.

COLOR BOOK

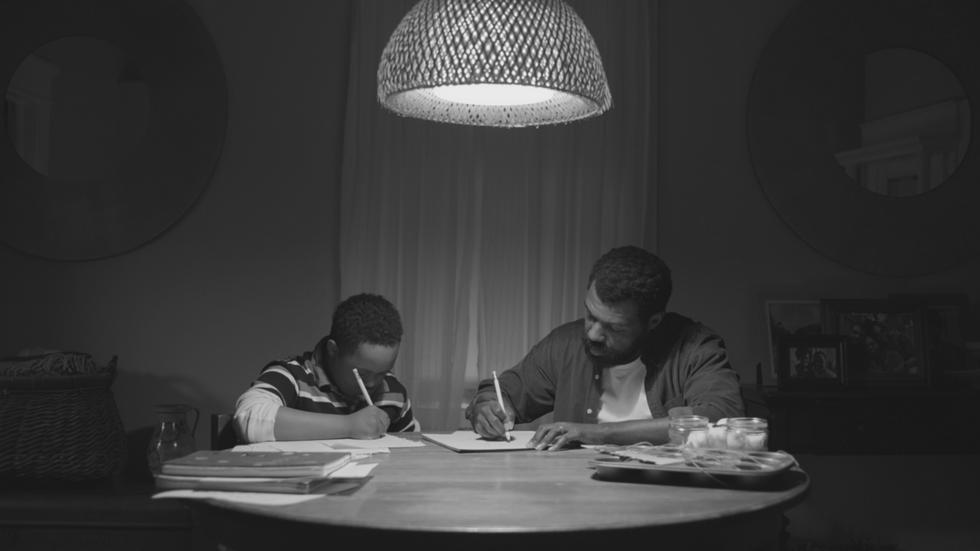

Mason (Jeremiah Daniels) is 11-years-old, loves baseball and drawing in his notebooks, and has Down syndrome. The latter makes it just a bit more difficult for his father, Lucky (William Catlett), to communicate easily with him, particularly following the unexplained death of his wife Tammy (Brandee Evans); within just a handful of seconds, the opening scene of Color Book, in which Tammy helps her son string together a necklace, contrasts her seemingly infinite patience with Lucky’s decidedly shorter fuse. Still reeling from Tammy’s loss, Lucky decides to try connecting with his son through the sport they both love, taking a friend up on an offer to attend a baseball game. Over the course of an afternoon, the pair journey across downtown Atlanta to get to the stadium, but they are beset by setback after setback, from their car breaking down, to losing each other on the train.

Color Book is written and directed by David Fortune, who won $1 million dollars to make his feature film in the 2023 Tribeca Film Festival’s AT&T Presents: Untold Stories competition, which gives filmmakers from historically underrepresented groups the chance to pitch their movies for a chance to received funding and mentorship opportunities. His film, in which virtually all of the speaking roles are granted to Black performers, delivers on portraying a side of Blackness that isn’t frequently depicted in mainstream media: a struggling but no less devoted father, an exuberant child who derives pleasure from something as simple as a balloon he associates with his mother or the act of coloring, the tender bond between them and the kind people who help them along the way with simple but meaningful gestures.

As tired as the dead mom trope is, it’s hard not to be won over by the winning performances from the two leads. Catlett in particular ably embodies his character’s many roiling emotions simultaneously (frustration, anger, guilt, despair), wearing his weariness on his face. Nikolaus Summerer’s luminous black-and-white cinematography, which recalls classic road-type narratives with a sharpness that doesn’t render it as overly nostalgic, is an added bonus. On paper, the scrapes the duo get involved with sound potentially ripe for comedy, but Fortune leans into the dramatic stakes instead. A baseball game isn’t the only thing on the line here; it’s proving one’s merit as a good parent. Color Book makes tidy work of its messy characters, but it undeniably understands that just doing your best, when the attempt comes from a place of love, is enough.

Color Book had its world premiere at the 2024 Tribeca Film Festival on June 8. Runtime: 98 minutes.

BITTERROOT

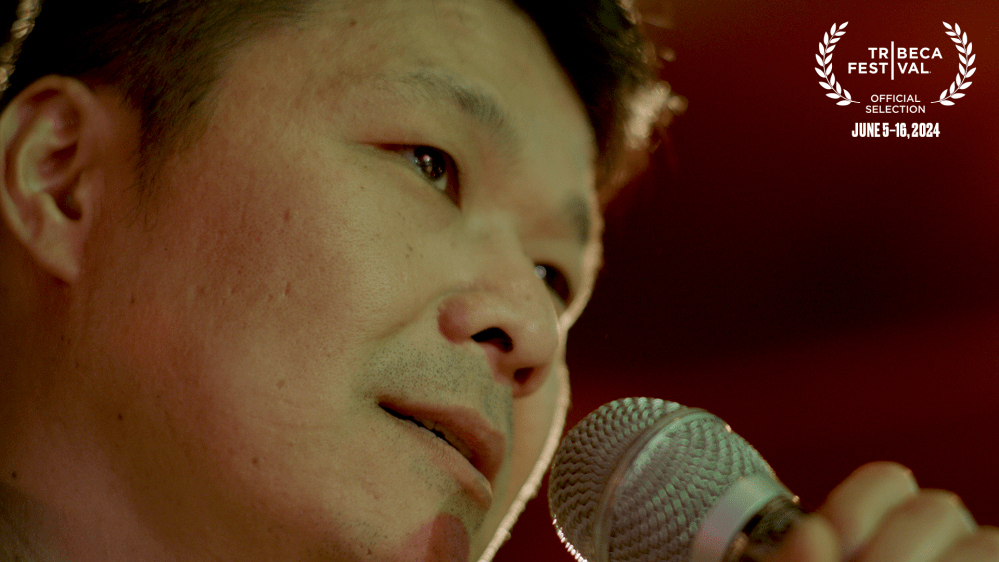

Family expectations are a heavy burden to bear, so easy to crumble under the weight of and lose your sense of self in. Six months after his divorce, Lue (Wa Yang), a middle-aged Hmong man, moves in with his mother in rural Montana, trying to care for her and her garden while also working a maintenance job and selling produce at a local farmer’s market. When he suddenly loses his job, Lue takes up extra work foraging in the forests around where he lives; all the while his friends, family, and especially his widowed mother Song (Qu Kue) do everything in their power (including resorting to spiritual rituals and seeking guidance from their ancestors) to get him to find another wife and settle down, so he can fulfill what they consider to be his main purpose on this planet: to have children and perpetuate his family line.

Writer and director Vera Brunner-Song’s Bitterroot looks at this mid-life crisis through a contemplative lens. Dialogue is sparse, but that approach goes a long way toward emphasizing Lue’s aimlessness and loneliness, from his days spent rummaging about in the woods to his nights spent drinking and performing karaoke at a local bar. At times, this works against the film, holding the viewer back from Lue’s inner conflict, especially as the focus is occasionally split between his perspective and that of his mother trying to find a wife for her son. When there is dialogue, it is sometimes a bit clumsy and heavy-handed, made more obvious by some amateurish supporting performances. In this instance, the merging of non-professional and professional actors doesn’t consistently gel, even with such a rugged landscape serving as the backdrop to the action; Montana’s natural beauty is gorgeously captured by cinematographer Ki Jin Kim, the setting (a seemingly unusual one to find a pocket of Hmong people in, despite the high number of transplants from Asia to the U.S.) serving to heighten the characters’ diaspora.

Details about Lue’s past— the reasons for his divorce, for instance— are sparse, but unravel throughout the film at a gradual pace that increases both the intrigue and the emotional weight (a scene late in the movie where Lue picks up and stares at a particular photo is truly gut-wrenching when we realize what we’re looking at). The source of the friction between Lue and Song (he even lies to his mother for a time about being laid off) may be specific to their culture and beliefs and feel outmoded to others, but there’s a lot of universality in a mother who just wants what’s best for her son, and a son who just wants to be accepted while leading his own life. Bitterroot’s portrayal of that conflict is about as low-stakes and calming as tending a garden, but it’s no less affecting.

Bitterroot had its world premiere at the 2024 Tribeca Film Festival on June 6. Runtime: 85 minutes.